Contradictions, however, are part of life, not merely a matter of conflicting [historical] evidence. I would ask the reader to expect contradictions, not uniformity. No aspect of society, no habit, custom, movement, development, is without cross-currents. … No age is tidy or made of whole cloth.

—Barbara W. Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, xxiii

Author: Jonathan Wilson

How Should We Then and Now: Ep. 1 (The Roman Age)

This is the first regular installment in a series of posts as I rewatch a 1977 documentary film series called How Should We Then Live? If you haven’t already seen it, I strongly recommend starting with the project introduction. Today’s episode is “The Roman Age.” (Because I’m still introducing key aspects of the overall series, today’s post is significantly longer than most will be. I hope you’ll bear with me.)

Last week, we talked about why Francis Schaeffer’s 1977 film series How Should We Then Live is important. Now let’s settle in to watch the first episode.

From the moment I began rewatching How Should We Then Live for this blog series, three things stood out.

First: It’s very seventies.

Continue reading “How Should We Then and Now: Ep. 1 (The Roman Age)”How Should We Then and Now: Introduction

This is the beginning of a series of weekly posts as I rewatch a 1977 documentary film series called How Should We Then Live? The first regular installment was posted the following Thursday.

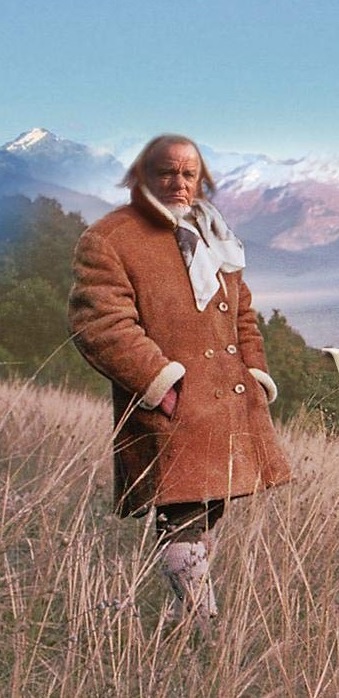

In the years after Time Magazine profiled him as a missionary to the “painters, writers, actors, singers, dancers and beatniks” of Europe in the 1960s, Francis A. Schaeffer IV cut a striking figure.

By the late 1970s, wearing knickerbockers and turtlenecks, with collar-length hair and a bushy goatee, Francis Schaeffer looked a bit like a shepherd who had come inside for a poetry reading—which I suppose is, metaphorically speaking, precisely what he was. He spoke in a soft, hoarse tenor. His accent had become unplaceably transatlantic without quite losing the sound of working-class Germantown, Philadelphia. In photographs and films, he always looked a bit sad.

And, of course, Francis Schaeffer had made a new life in French-speaking Switzerland. That was a very long way, in more than one sense, from the fundamentalist Presbyterian churches that had provided his early intellectual formation in America’s future rust belt.

Though he struggled with incapacitating depression and an explosive temper, Francis Schaeffer, together with his wife Edith and their children, had opened their home to a little international community, aiming to share the life of the mind. Established in 1955, L’Abri, meaning “The Shelter,” had become a kind of Protestant ashram, combining aspects of a youth hostel, a utopian community, and a religious study group.

There, in chalets in the foothills of the Swiss Alps, the Schaeffers offered hospitality—but also, as they saw it, uncompromising lessons in the truth—to intellectual wanderers. They promised “honest answers to honest questions,” which became a catchphrase. For if “Christianity is truth,” Francis reasoned in 1974, it must have answers about “every aspect of life”—but this required “that we have enough compassion to learn the questions of our generation” in the first place.

By the 1980s, this paradoxical Pennsylvanian in Switzerland—whom his own daughter would jokingly call “a very odd man”—had become one of the most important writers and speakers in America’s evangelical movement. By extension, he exercises a crucial influence on U.S. politics to this day. (L’Abri still exists, too, with satellite study centers as far away as Brazil, South Africa, and South Korea. The name, by the way, is pronouced “lah-BREE.”)

Here’s what interests me for the purposes of this blog: Between 1974 and 1977, Francis Schaeffer, a preacher with no relevant academic training, attempted an ambitious interpretation of European cultural history in the form of a documentary film series and a companion book.

Continue reading “How Should We Then and Now: Introduction”“Essentially an Evil Thing”

In the last few days, several European conversations converged for me in a troubling way.

Historic anniversaries played a role. This Saturday was the anniversary of V-E Day for most western nations. And the next day, which was Victory Day in Russia, Vladimir Putin delivered a speech that western media found threatening. In some pockets of social media, I found scattered debates about how to remember the Soviet Union’s outsized role in Nazi Germany’s defeat. Last Wednesday, meanwhile, had been the bicentenary of Napoléon Bonaparte’s death. Marking that day, Emmanuel Macron laid a wreath at the dictator’s grave, delivering a speech that lightly acknowledged some of Napoléon’s crimes yet also celebrated his “political will” and “taste for the possible”—as if murdering people on a continental scale were a self-actualization exercise.

In the Guardian yesterday, the columnist Kenan Malik—with one eye on recent British debates about how to remember the imperialist-but-antifascist Winston Churchill—brought together various conversations when he implicitly praised Macron’s speech as a refusal “to paint heroes and villains in black and white, to simplify the past as a means of feeding the needs of the present.”

Reading the text of Macron’s speech myself, though, I find that simplifying the past to feed the needs of the present is precisely what the French president was doing.

Continue reading ““Essentially an Evil Thing””“Ignorance of History Serves Many Ends”

The more time I spent in Oxford, the more I realised how colonialism had remade the entire material and intellectual world of the British empire, especially its most elite university. Oxford is strewn with tributes to men of empire who have scholarships, portraits, busts, engravings, statues, libraries and even buildings dedicated to their memory. …

From the start, the quest for knowledge of Africa was motivated by the aim of conquest. Even today, African studies has an air of the 1884 Berlin Conference, which heralded the ‘Scramble for Africa’—but instead of European powers claiming and trading different parts of the continent, it’s mostly white scholars staking out their territory and asserting expertise over ethnicity in Kenya, democracy in Ghana or refugees in Uganda. After I stayed on at Oxford to pursue a doctorate, I began attending African studies conferences throughout the UK, only to find mostly white scholars talking to predominantly white audiences.

In other words, I was surrounded in Oxford not by the ghosts of colonialism, but by its living dead. As at [St. George’s College in Harare], colonialism at Oxford had never really ended, and couldn’t. It wasn’t a period that had passed, but a historical mass that bent everything around its gravity.

—Simukai Chigudu, “‘Colonialism Had Never Really Ended’: My Life in the Shadow of Cecil Rhodes'”

To Teach in Narrative, Think in Scenes

When I started teaching history on my own—working from my own syllabus rather than assisting someone else—I was thrown into a college U.S. history course just a couple of weeks before the semester started. I was still a graduate student, though I had my master’s degree, and I was replacing another adjunct instructor at the last minute. (I would eventually get to meet her at a conference. She’s nice.) She had chosen a set of textbooks that I’d never heard of, much less seen, and I found the department’s description of the course bizarre.

When I walked into the classroom, which had broken desks and obvious water damage, I still didn’t have access to my university email account or the university library. For the first few days, I had to ask the department secretary to come unlock the classroom computer any time I planned to use it.

Did I mention this was going to be the first time I had ever taught my own solo course?

I won’t keep you in suspense: That semester did not end up being my best work.

Continue reading “To Teach in Narrative, Think in Scenes”Testing the West at Howard University: Thoughts on a Very Strange Op-Ed

I have mixed feelings about a widely shared Washington Post opinion essay published Monday by Cornel West and Jeremy Tate. The current headline: “Howard University’s removal of classics is a spiritual catastrophe.”

Continue reading “Testing the West at Howard University: Thoughts on a Very Strange Op-Ed”The Conservatism of My Teaching: Seven Elements

There’s something I want to get off my chest. It’s about whether Blue Book Diaries is a left-wing blog, and about whether my teaching is left-wing instruction.

I have been ruminating on this since I discovered recently that a stranger on Facebook has repeatedly called me a “commie”—ironically, because I said the Trump era is a good time to teach history.

Similarly, my most popular post here, which has drawn more than 10,000 hits, has been denounced as leftist propaganda. After I posted it in June, during the protests after George Floyd’s death, it elicited a stream of angry messages. An email I received from Greg, who was using an IP address in West Texas, will give you a pretty good idea of the general mood. Here is the full text:

I’m not sure how extensive someone’s intellectual exploration can be if something I wrote is the leftmost thing they’ve encountered. Nevertheless, that seemed to be a common impression among those who were displeased—even though the blogpost in question is overtly patriotic and even pro-military.

To be thus politically pigeonholed, in such disregard for the actual content of work I spend a lot of time crafting? It rankles. I have been successfully rankled. And I think it’s time for me to address this problem.

What I write today is unlikely to have much positive effect on Greg—or on anybody else who believes insurgent is an ethnonym. But it might be soothing to other history teachers who are feeling a bit out of joint.

You see, I suspect that many of us working in U.S. educational institutions see our own work as deeply conservative, at the same time that today’s organized political right is attacking us for supposedly “hating our country” and “breeding contempt for America’s heritage.”

Such attacks notwithstanding, many of us are proudly doing exactly what our predecessors have done for generations. We are teaching history in a politically conscious but nonpartisan way, out of a sense of respect for the past and concern for our communities in the present, and we are using methods pragmatically adapted to the needs of our students and the results of historical scholarship.

With that in mind, let me identify some of the aspects of my own history teaching that I think are fundamentally conservative.

But first, I should explain what that term means.

Continue reading “The Conservatism of My Teaching: Seven Elements”Teaching Controversial History: Four Moves

Inspired by some recent conversations and experiences, I have been thinking about how I approach the task of teaching controversial topics.

Much of my approach, I think, is directly inspired by having been a fairly prickly kind of student myself. I still see a lot of myself in students who aren’t prepared to buy what their instructors are hoping to sell. (Let’s assume, for the sake of simplicity, that we instructors are correct, though of course that is not universally the case.)

I think I can reduce my approach to four basic instructional moves. These moves strike me as both pragmatic and principled; I make these moves because they tend to work, but they work because they’re the morally right thing to do anyway.

Continue reading “Teaching Controversial History: Four Moves”The Invisible Storyteller

A storyteller should be invisible, as far as I’m concerned; and the best way to make sure of that is to make the story itself so interesting that the teller just … disappears. When I was in the business of helping students to become teachers, I used to urge them to tell stories in the classroom—not read them from a book, but get out and tell them, face to face, with nothing to hide behind. The students were very nervous until they tried it. They thought that under the pressure of all those wide-open eyes, they’d melt into a puddle of self-consciousness. But the brave ones tried it, and they always came back next week and reported with amazement that it worked, they could do it. What was happening was that the children were gazing, not at the storyteller, but at the story she was telling. The teller had become invisible, and the story worked much more effectively as a result.

—Philip Pullman, “Magic Carpets: The Writer’s Responsibilities,” Society of Authors’ Children’s Writers and Illustrators Group Conference, Leeds, Sept. 2002; in Daemon Voices: On Stories and Storytelling, ed. Simon Mason (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018), 9-10. Ellipsis in original.