A few months ago, I made available a PowerPoint template called Retrovisibility, which I’ve been using in history courses for many years. Today, I’m releasing Dateline, a completely new template for classes in humanities and social science disciplines. I’m publishing it under a Creative Commons license for free noncommercial use.

Uses

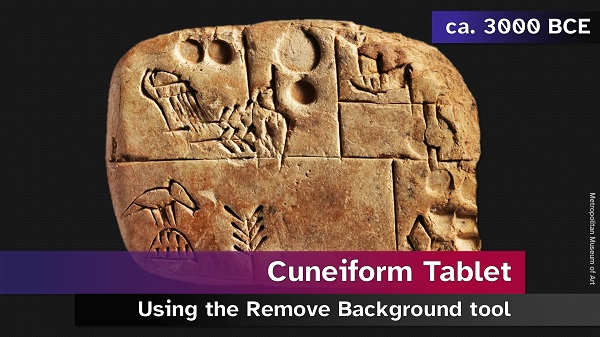

Dateline is designed to help instructors prioritize images and multimedia, not text. Inspired by the layouts used in television news, it includes subtle dynamic elements and friendly colors. It’s designed for use with the Braille Institute’s open typeface (or font) Atkinson Hyperlegible for high readability.

A distinctive element in Dateline is the inclusion of a placeholder for dates or date ranges. This is likely to be particularly useful to history teachers. But it may also be useful to instructors in other social science and humanities disciplines. (Potential uses in less chronological disciplines include, e.g., adapting APA citation conventions, listing page ranges instead of dates, displaying copyright notices, etc.) Text-centered slide layouts include a footnote element instead of the date placeholder.

Download

Dateline v. 0.9 (2023-05-06) (CC BY-NC 4.0) (6.85 MB)

Because WordPress.com does not host PowerPoint template (.potx) files, the template is provided as a presentation (.pptx) file instead. You will need to download it, delete the sample slides, and save it as a presentation template. Please click here for instructions about saving a PowerPoint template on your own computer.

This template is provided as-is. I cannot guarantee how it will work for any user.

Specifications

The best results are likely if you use a recent desktop edition of Microsoft PowerPoint on a Windows PC (both to prepare your presentation and to project it in the classroom). The template is designed for widescreen (16:9) displays.

Important: Dateline results in large file sizes for the slideshows you create. This is particularly true if you choose to include high-resolution background images. A slideshow for an hourlong presentation may become a 50+ MB file. This will be impractical for many users.

For the most consistent results, you should install Atkinson Hyperlegible on any computer you use to prepare slideshows with this template. Installing this font on your classroom computer, however, should not be necessary as long as you embed the font when you save a slideshow. (If you aren’t familiar with what it means to embed a font in a PowerPoint presentation, I recommend learning.)

If you use Dateline on computers running Windows, it should embed Atkinson Hyperlegible in your presentations by default when you save them. However, embedding fonts is possible for only some Mac users.

Feedback

If you’ve used Dateline and are willing to offer comments, please use the contact form. I’m grateful for any information that could make this template better.