Every hero needs both an inner and an outer problem. In developing fairy tales for Disney Feature Animation, we often found that writers, in the early drafts, would give the heroes a good outer problem: Can the princess manage to break an enchantment on her father who has been turned to stone? Can the hero get to the top of a glass mountain and win a princess’s hand in marriage? Can Gretel rescue Hansel from the Witch? But sometimes writers neglected to give the characters a compelling inner problem to solve as well.

Characters without inner challenges seem flat and uninvolving, however heroically they may act. They need an inner problem, a personality flaw or a moral dilemma to work out. They need to learn something in the course of the story: how to get along with others, how to trust themselves, how to see beyond outward appearances. Audiences love to see characters learning, growing, and dealing with the inner and outer challenges of life.

—Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 4th ed. (Studio City, Ca.: Michael Wiese Productions, 2020), 105

Category: Commonplace

“Clear-Eyed, Nuanced, and Frank”

This morning, dozens of scholarly and educational organizations in the United States—including PEN America, the American Historical Association, the American Association of University Professors, the Association of American Colleges and Universities, and the American Federation of Teachers—have signed a joint statement condemning broadly-worded bills that aim to curtail discussions of racism and history in schools and colleges.

First, these bills risk infringing on the right of faculty to teach and of students to learn. The clear goal of these efforts is to suppress teaching and learning about the role of racism in the history of the United States. Purportedly, any examination of racism in this country’s classrooms might cause some students ‘discomfort’ because it is an uncomfortable and complicated subject. But the ideal of informed citizenship necessitates an educated public. Educators must provide an accurate view of the past in order to better prepare students for community participation and robust civic engagement. Suppressing or watering down discussion of ‘divisive concepts’ in educational institutions deprives students of opportunities to discuss and foster solutions to social division and injustice. Legislation cannot erase ‘concepts’ or history; it can, however, diminish educators’ ability to help students address facts in an honest and open environment capable of nourishing intellectual exploration. Educators owe students a clear-eyed, nuanced, and frank delivery of history so that they can learn, grow, and confront the issues of the day, not hew to some state-ordered ideology.

—Joint Statement on Legislative Efforts to Restrict Education about Racism and American History, June 16, 2021

Expect Contradictions

Contradictions, however, are part of life, not merely a matter of conflicting [historical] evidence. I would ask the reader to expect contradictions, not uniformity. No aspect of society, no habit, custom, movement, development, is without cross-currents. … No age is tidy or made of whole cloth.

—Barbara W. Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, xxiii

“Ignorance of History Serves Many Ends”

The more time I spent in Oxford, the more I realised how colonialism had remade the entire material and intellectual world of the British empire, especially its most elite university. Oxford is strewn with tributes to men of empire who have scholarships, portraits, busts, engravings, statues, libraries and even buildings dedicated to their memory. …

From the start, the quest for knowledge of Africa was motivated by the aim of conquest. Even today, African studies has an air of the 1884 Berlin Conference, which heralded the ‘Scramble for Africa’—but instead of European powers claiming and trading different parts of the continent, it’s mostly white scholars staking out their territory and asserting expertise over ethnicity in Kenya, democracy in Ghana or refugees in Uganda. After I stayed on at Oxford to pursue a doctorate, I began attending African studies conferences throughout the UK, only to find mostly white scholars talking to predominantly white audiences.

In other words, I was surrounded in Oxford not by the ghosts of colonialism, but by its living dead. As at [St. George’s College in Harare], colonialism at Oxford had never really ended, and couldn’t. It wasn’t a period that had passed, but a historical mass that bent everything around its gravity.

—Simukai Chigudu, “‘Colonialism Had Never Really Ended’: My Life in the Shadow of Cecil Rhodes'”

The Invisible Storyteller

A storyteller should be invisible, as far as I’m concerned; and the best way to make sure of that is to make the story itself so interesting that the teller just … disappears. When I was in the business of helping students to become teachers, I used to urge them to tell stories in the classroom—not read them from a book, but get out and tell them, face to face, with nothing to hide behind. The students were very nervous until they tried it. They thought that under the pressure of all those wide-open eyes, they’d melt into a puddle of self-consciousness. But the brave ones tried it, and they always came back next week and reported with amazement that it worked, they could do it. What was happening was that the children were gazing, not at the storyteller, but at the story she was telling. The teller had become invisible, and the story worked much more effectively as a result.

—Philip Pullman, “Magic Carpets: The Writer’s Responsibilities,” Society of Authors’ Children’s Writers and Illustrators Group Conference, Leeds, Sept. 2002; in Daemon Voices: On Stories and Storytelling, ed. Simon Mason (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018), 9-10. Ellipsis in original.

The False Choices of Pedagogy Critics

Framing the instructional situation as a set of either-or choices, such as abandoning textbooks in favor of primary sources or substituting student inquiry projects for teachers’ lectures, ignores the perennial challenges that history students and, consequently, history teachers face in trying to learn history and develop historical understanding. History is a vast and constantly expanding storehouse of information about people and events in the past. For students, learning history leads to encounters with thousands of unfamiliar and distant names, dates, people, places, events, and stories. Working with such content is a complex enterprise not easily reduced to choices between learning facts and mastering historical thinking processes. Indeed, attention to one is necessary to foster the other.

—Robert B. Bain, “‘They Thought the World Was Flat?’,” in M. Suzanne Donovan and John D. Bransford, eds., How Students Learn: History in the Classroom (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2005), 180

“Remember the Roots of Our Discipline”

In a distracted world …, and at a moment when there seems to be widespread public doubt about whether to continue supporting the study of the past as this organization has traditionally understood that activity, what is the future of history? There are many answers to this question, of course, and it is the job of the American Historical Association—and all of us—to offer those answers as effectively as we can to defend in public the continuing importance of history both in the United States and in the wider world. But for me, there is one answer that is arguably the most basic of all, and that is, simply: storytelling. We need to remember the roots of our discipline and be sure to keep telling stories that matter as much to our students and to the public as they do to us. Although the shape and form of our stories will surely change to meet the expectations of this digital age, the human need for storytelling is not likely ever to go away. It is far too basic to the way people make sense of their lives—and among the most important stories they tell are those that seek to understand the past. …

[T]he undergraduate classroom, far more than the graduate seminar, is where we take the results of our monographic research and place them in a much larger interpretive frame where we can show our students—and, by extension, our non-professional readers and ourselves—the larger meanings of our work. Original research is of course indispensable and lies at the cutting edge of disciplinary growth and transformation. But no one else will ever know this if we fail to come back from the cutting edge to integrate what we have learned into the older and more familiar stories that non-historians already think they know and care about. This is where we join other historical storytellers—journalists, novelists, dramatists, and filmmakers, as well as our academic colleagues in all the other historical disciplines—to keep asking what the past means and why ordinary people should care about it.

—William Cronon, “Storytelling” (presidential address to the American Historical Association), New Orleans, 2013

U.S. Adults Want Teachers Vaccinated

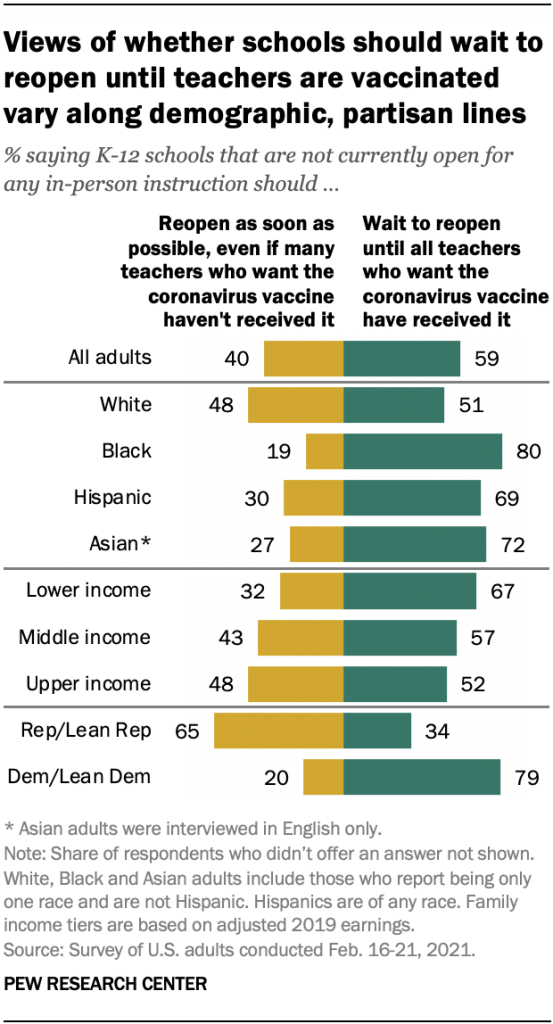

According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in mid-February, adults in the United States have grown more concerned (since July 2020) about the effects of K-12 school closures on student academic progress. They have grown less concerned about the risk of SARS-CoV-2 spreading among students or teachers.

The risk of losing academic ground is now the leading factor cited by American adults as a determinant of whether schools should return to in-person instruction—ahead of students’ emotional wellbeing as well as pandemic transmission risks.

However, almost three in five American adults still say that K-12 school buildings should not reopen for in-person instruction until teachers have the chance to get vaccinated.

That becomes an overwhelming consensus among Black, Hispanic, Asian, and lower-income adults, as well as among Democrats, all of whom say, at least two-to-one and as much as four-to-one, that teachers should be vaccinated before K-12 schools return to in-person instruction.

In other words, statistically, the most vulnerable Americans are also the ones who most want teachers vaccinated before K-12 school buildings reopen.

You can find the news release about the report, along with links to the full data, at the Pew Research Center’s website.

A Century of PPE (the Other One)

I missed this article when it appeared in 2017, but I’ve just caught up with it thanks to the Guardian’s excellent Audio Long Read podcast.

Last year marked the centenary of PPE—not personal protective equipment, but the Oxford undergraduate concentration in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. As the headline of Andy Beckett’s story puts it, this is the “degree that runs Britain,” the university education of the UK’s political establishment.

Oxford PPE is more than a factory for politicians and the people who judge them for a living. It also gives many of these public figures a shared outlook: confident, internationalist, intellectually flexible, and above all sure that small groups of supposedly well-educated, rational people, such as themselves, can and should improve Britain and the wider world.

In Beckett’s telling, PPE’s history embodies the paradox or tragedy of western social democracy since the early twentieth century: What began in egalitarianism and emergency reform, in the wake of World War I and its attendant revolutions, became the province of a complacent rationalist-technocratic elite.

From the start, for some ambitious students, Oxford PPE became a base for political adventures as much as a degree. Hugh Gaitskell arrived at the university in 1924, a public schoolboy with no strong ideological views. There he fell under the spell of GDH Cole, an intense young economics tutor and socialist – the first of many such PPE dons – who was ‘talked about’, Gaitskell wrote excitedly later, ‘as a possible leader of a British revolution’. …

Yet during the postwar years, PPE gradually lost its radicalism. … By the late 1960s, despite the decade’s global explosion of protest politics, PPE was still focused on more conventional, sometimes insular topics. ‘The economics was apolitical,’ [Hilary] Wainwright remembers, ‘questions of inequality were not addressed. In politics, the endless tutorials seemed so unrelated to the crises that were going on. PPE had become a technical course in how to govern.’

Today, of course, PPE is the quintessential training for an elite that many observers consider moribund and insular in an age of global reactionary populism, hyperconcentrated capital, and institutional failure.

It seems to me that Andy Beckett’s essay offers a number of interesting points for American educators today to reflect upon. Many of us pride ourselves on educating “future leaders,” or something similar, and offer an expensive education to a relatively small section of U.S. society while also espousing egalitarian values. The history of PPE suggests what may come of such a paradox, for better or for worse.

The essay is especially interesting when we consider the nature of PPE as a course of undergraduate study:

‘PPE thrives,’ says [David] Willetts, a former education minister who is writing a book about universities, ‘because a problem of English education is too much specialisation too soon, whereas PPE is much closer to the prestigious degrees for generalists available in the United States.’

You can read the full story here, or you can listen to a narrator reading it—along with a new audio introduction by the author, who wryly observes that Oxford’s PPE might be relevant to Britain’s failures with respect to medical PPE during the current pandemic.

The Political Consciousness of the Teachers Who Made Black History Month

The creation of Negro History Week did not occur in a vacuum. It reflected a continuum of consciousness among Black educators, channeling an intellectual and political tradition long practiced in the private spaces of their classrooms. This class of teachers placed the needs of their students above protocols imposed by white school leaders. …

[T]hese educators insisted on the importance of providing students with cultural armor to repudiate the racial myths reflected in the nation’s laws, social policies, and American curriculum.

—Jarvis R. Givens, “The Important Political History of Black History Month”