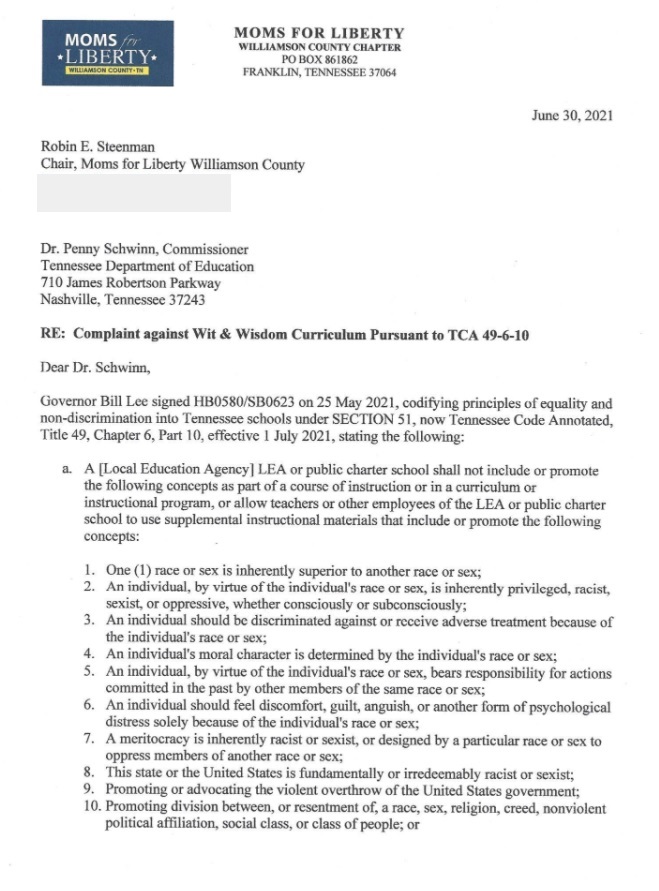

In the state of Texas, a new law took effect on September 1, limiting what public social studies teachers can teach. The bill passed in the state legislature on an almost perfect party-line vote.

Among other things, the law, House Bill 3979, mandates that in required courses,

a teacher who chooses to discuss [a particular current event or widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs] shall, to the best of the teacher’s ability, strive to explore the topic from diverse and contending perspectives without giving deference to any one perspective.

Today, NBC News has reported on the effect this law is having in the Dallas/Forth Worth suburb of Southlake, where the school district is already embroiled in a political battle over racism. The district’s curriculum director was recently recorded (surreptitiously) during a training session with teachers, acknowledging their fears about the law. She told them,

We are in the middle of a political mess. And you are in the middle of a political mess. And so we just have to do the best that we can. … You are professionals. … So if you think the book is O.K., then let’s go with it. And whatever happens, we will fight it together.

But she added, giving an example of a potential conflict,

As you go through, just try to remember the concepts of [H.B.] 3979, and make sure that if you have a book on the Holocaust, that you have one that has an opposing—that has other perspectives.

Teachers heard on the recording reacted with shocked disbelief, speculating that this directive would apply to a book like Number the Stars, a widely taught historical novel about a Jewish family in Nazi-occupied Denmark.

She said, “Believe me, that’s come up.”

EDIT: On social media, many people have been attacking the administrator for supposedly suggesting it could be legitimate to present students with “opposing” sides on the Holocaust. I think they probably have misinterpreted what happened here.

Southlake has been at the center of a very public controversy over racism at its high school. That is presumably why NBC News was provided with this audio recording in the first place; NBC has been covering this situation in depth. In this context, Southlake school district is likely to have been targeted by far-right extremists; that’s how the world often works today.

In the audio released by NBC, the curriculum director is heard clearly indicating that she finds H.B. 3979 outrageous, committing herself to support teachers when they choose to teach controversial books. But she also provides teachers with strategic advice for protecting themselves against the law.

Because the text of H.B. 3979 does not discriminate against far-right extremist ideas.

In my reading, it is significant that the curriculum director corrected herself when she started to talk about supplementing the curriculum with “a book that has … an opposing” perspective on the Holocaust, switching to “a book … that has other perspectives” on the Holocaust.

Remember the actual language of H.B. 3979: When a teacher discusses a controversial social studies topic, they must “explore the topic from diverse and contending perspectives without giving deference to any one perspective.” Given that language, teachers targeted by extremists would be providing themselves with legal cover for teaching the Holocaust truthfully if they could find “diverse and contending perspectives”—which could mean a lot of things other than Holocaust denial or approval—to include in the discussion.

And given Southlake’s recent history in the public eye, I’m inclined to believe the curriculum director, at least in a general way, when she says this issue has “come up” already.

I certainly hope that any court would rule that the Holocaust does not qualify as a “widely debated” topic. (“Currently controversial,” unfortunately, would include, by definition, virtually anything that resulted in a teacher being targeted.) But teachers and school districts do not have infinite resources for going through the process of finding out how courts will rule when they interpret bad laws.

A second EDIT to add: It is also worth understanding the internal dynamics of Southlake’s school district, to the extent they are publicly known.

The Dallas Morning News and the Forth Worth Star-Telegram report that a fourth-grade teacher there—a Carroll ISD 2020 “teacher of the year,” in fact—was recently the target of political harassment for having in her classroom a book called This Book Is Anti-Racist. The politicians on the school board—including two who had received donations from the parents’ PAC who complained—voted to reprimand the teacher for doing her job. In making this decision, the politicians were overruling the school administration, who had investigated the complaints and had cleared the teacher of wrongdoing.

In an environment like this, for anyone to attack a school administrator for trying to protect teachers against political harassment, as the curriculum director in the most recent controversy did, is to compound the chilling effects of Texas law, making it more dangerous to be a history teacher in Texas, not less.