In the Washington Post yesterday, the data journalist Philip Bump highlighted some results of a March 2022 edition of the Grinnell College National Poll. His article focuses on respondents’ views of what should be taught in American public schools.

The poll shows that Republicans and Democrats differ significantly in their level of expressed support for (in particular) sex education and attempts to instill patriotism—though clear majorities in both parties actually say they support both. Thus, the current headline, “Democrats want to teach kids sex education. Republicans want to teach them patriotism”—is misleading, though it’s grounded in truth.

What caught my eye was the entry for history.

Unsurprisingly, strong majorities in both major parties believe that public schools should teach history. But I couldn’t help noticing that support for teaching history was ever-so-slightly lower among Democratic respondents.

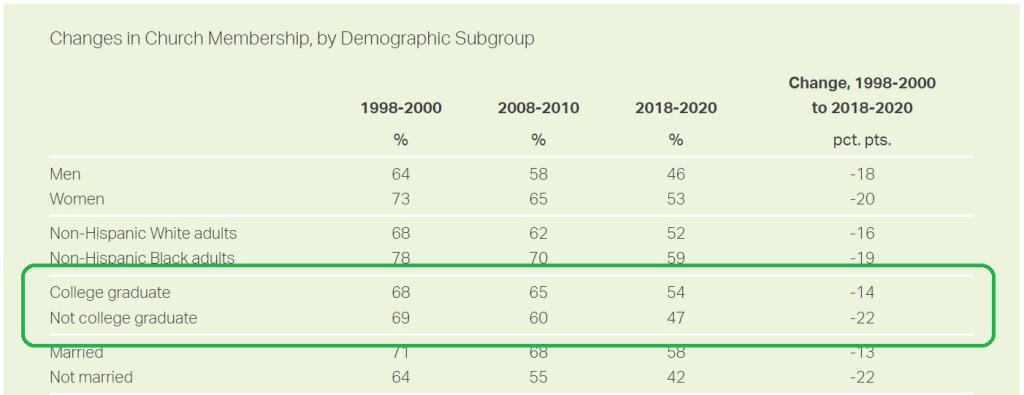

That’s consistent with what another major survey found in 2020: American conservatives were more likely than liberals (92% to 84%) to say that teaching U.S. history to children is very important, and they’re also more likely (44% to 30%) to say they wish they’d had more American history courses in school.

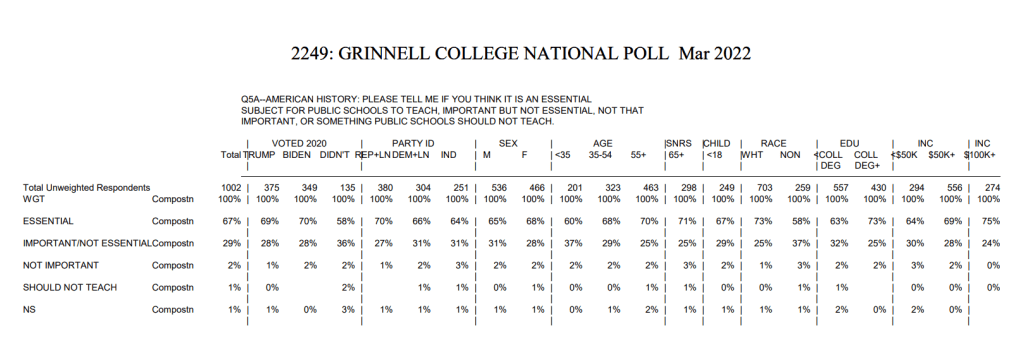

Curious, I dug up the new Grinnell poll’s topline results.

I found that this poll, too, actually asked about American history, not history in general. And interestingly, although there was slightly lower expressed support for teaching U.S. history among Democrats than among Republicans, there wasn’t any significant difference between 2020 Trump and Biden voters.

What conclusions should we draw from this? I really have no idea. Probably, we shouldn’t draw any conclusions at all. Anyway, all the potent debates of our moment are about what should be taught in public schools as American history, not whether American history should be taught.

But I know that if I ever see support for teaching U.S. history in public schools drop significantly, among either Democrats or Republicans, I’ll have a new big thing to worry about.