Like a lot of other Americans, I grew up in a conservative subculture that assumed college would be a hostile environment. Many of my acquaintances took for granted that America’s overwhelmingly liberal or left-wing professors are tempted to discriminate against conservative students.

I have reason to believe this expectation hasn’t gone away. Actually, it seems to be more widely shared by conservative Americans today than it was then. It’s a big part (though only part) of what people are talking about when they debate liberal or left-wing “bias” on campus. But is there evidence for it, beyond anecdotes and rumors?

This spring, a team of researchers led by a self-described “lifelong Republican” released a working paper called “Is Collegiate Political Correctness Fake News?: Relationships between Grades and Ideology.” (A working paper presents research results that have not yet been formally vetted by a peer-reviewed publication.)

Analyzing survey responses from more than seven thousand students who attended U.S. four-year universities from 2009 to 2013, the researchers (Matthew Woessner, Robert Maranto, and Amanda Thompson) looked for relationships among students’ self-reported political views and grade point averages.

What they found was … complicated.

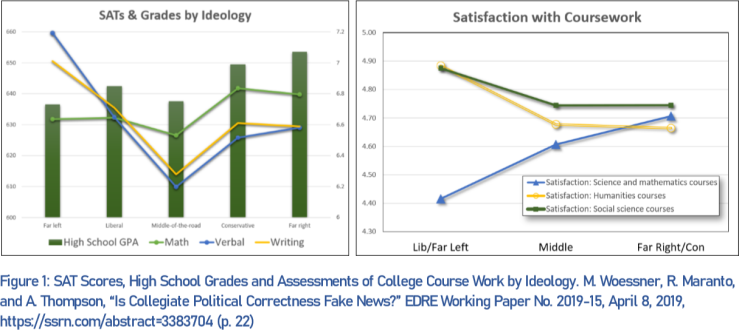

Some of the complexity is captured in a writeup by Jill Barshay for the Hechinger Report. Overall, the study says conservatives do get lower grade point averages, but not much lower: After the researchers controlled for factors like socioeconomic status and SAT scores, “the most conservative students earned grades that were less than a tenth of a grade point lower than those of the most liberal students on a conventional four-point scale.” As Barshay points out, “That’s a small fraction of the difference between a B (a 3.0) and a B-plus (a 3.3), for example.” And furthermore, the study finds that conservative students actually enjoy college more than liberals do.

When you dig further into some of the details, though, things get very interesting. Take the issue of abortion, for example. Barshay’s summary again:

Students who expressed pro-life views, generally a subgroup among conservative students, tended to report higher grades in both high school and college. However, the academic advantage for pro-life students disappeared at elite colleges. That could be a sign of a greater bias against pro-life students at highly selective colleges. But it’s also possible these [pro-life] students, whose survey responses indicated that they are good at delaying gratification, lose their relative advantage at highly selective colleges, where all students tend to delay gratification and work hard.

(In addition to greater skill at delaying gratification, the actual working paper speculates that pro-life students at non-elite colleges may also tend to benefit academically from the greater “social connectivity among students in Christian groups” in which they tend to be active [p. 9]. The researchers found that pro-life students not only get better grades than pro-choice students at most colleges, but also report higher satisfaction with their college experience [p. 11].)

The researchers examine a number of other factors and isolate other varieties of conservative opinion, too. It’s worth reading the full study to appreciate how careful their work is.

What’s the bottom line? The researchers’ conclusions are complex enough that they have been hailed both as vindication of conservative fears (“Paper: Professor Bias May Deflate Conservative College Students’ Grades,” says The Federalist) and as evidence against conservative fears (“A major study led by a lifelong Republican finds no evidence that professors are deliberately giving conservative students bad grades,” says Pacific Standard).

Both reactions are plausible, as long as they’re expressed with appropriate caveats.

Indeed, I think there’s material in the study to validate almost anybody’s prior beliefs about American colleges. The study’s full findings are so complex—one is tempted to say contradictory—that the authors conclude (p. 12) that “students who report valuing dissent and favoring restrictions on free speech report more favorable relationships with faculty” (emphasis added) than students who don’t.

That is, college students’ experiences reflect the same incoherence that all American political discourse sometimes involves.

The researchers themselves leave open the possibility that their study shows a slight overall faculty bias against conservative students. But they seem to favor other possible interpretations of the small GPA gap between liberal and conservative undergraduates. Indeed, they caution against the temptation to “cherry-pick” their findings, which “do not paint a picture of conservative students under siege.” Instead, they conclude,

[Conservative students] remain largely satisfied with their college education, and perform nearly as well as, if not better than, their liberal counterparts. While students’ political views may play a small role in their overall grades, success in college is more associated with measures of merit, and with demographic variables. Even if some students are the victims of unconscious bias in grading, these results suggest that academic readiness is a far more important predictor of success than students’ political views. (p. 13)

In other words, these researchers want to reassure us that college is basically fair.

But there’s still a small GPA discrepancy to explain, right? What’s going on, if there’s not at least a mild tendency among professors to discriminate against conservative students in their grading? Isn’t such a mild tendency still a problem?

Well, if you don’t read the report itself, it’s easy to miss the fact that it strongly implies that the biggest reason college experiences are different is that conservative and liberal college students tend to think differently.

Shocking, right?

I don’t mean that liberals and conservatives have different political opinions. I mean they tend systematically to have different ways of perceiving and studying the world.

Basically, the study seems to show that liberal students have an advantage in humanities and social science subjects (and in college overall), while conservatives have an advantage in math and natural science courses (and in high school overall).

In terms of students’ satisfaction with their experiences, this is reflected in the fact that liberals and leftists really, really like their humanities and social science courses but aren’t so fond of their math and science courses in college, while conservatives are quite happy with both.

If that’s true, it’s almost hilariously consistent with the conventional wisdom of both liberals and conservatives about their own cognitive dispositions.

The images below, which encapsulate the difference, are the two charts in Figure 1, “SAT Scores, High School Grades and Assessments of College Course Work by Ideology,” on the last page (p. 22) of the working paper:

Whatever else may be going on with liberal and conservative students’ GPAs, it seems likely that it has something to do with general differences in their mindsets, and probably with a lot of related cultural factors among students that will be hard for researchers to pinpoint.

My interpretation of the study leaves many unanswered questions. To state just a few: Are conservative professors better than liberal professors at making their humanities and social science courses interesting to conservative students? Is that an area in which liberal professors can improve? Does the college GPA discrepancy disappear (or reverse) when students have more conservative professors, or does it remain? Would the college GPA discrepancy disappear if conservative students were trained to be less suspicious of their humanities and social science courses in the first place? Do conservative students interested in the humanities and social sciences tend to become more liberal over time, and if so, why? Conversely, do liberal students interested in math and natural science tend to become more conservative? And, to look at the whole matter differently, should high school teachers be working harder to get liberal teenagers interested in math and natural science? (That seems like something liberals might want to think hard about.)

I’m not sure any of these questions has an obvious answer, and I can think of many others to explore.

But yeah, if this study is right, conservative students seem to be doing just fine in American colleges.

[…] Do conservative college students suffer lower grades because of their political views? After reading a new study on that question, Jonathan Wilson […]

LikeLike

[…] with research showing that conservative students in 2009-2013 (contrary to cherished myth) had very positive experiences with most of their college courses. It also seems consistent with research showing that, at least until 2016, a college education […]

LikeLike